Ever wondered why some dishes make your mouth water more than others? The secret often lies in a single molecule: monosodium glutamate, or MSG. Far from being just a controversial food additive, MSG is a gateway to understanding the elusive taste of umami, the “fifth taste,” and its profound impact on cooking, food science, and human taste perception. From traditional Japanese kitchens to global food industries, MSG has shaped the flavors we crave, elevating simple ingredients into complex, deeply satisfying dishes.

This article explores MSG in unprecedented depth, covering its discovery, chemistry, culinary applications, historical controversies, health considerations, scientific development, and the insights of chefs and doctors alike.

Chapter 1: Kikunae Ikeda – The Japanese Pioneer of Umami

The story of MSG begins in 1908, in Japan, when chemist Kikunae Ikeda set out to understand the unique flavor of kombu dashi, a broth made from kelp (kombu). Unlike sweet, sour, salty, or bitter tastes, the savory richness of this broth was elusive—full-bodied, long-lasting, and deeply satisfying. Ikeda suspected a chemical basis for this flavor.

Through painstaking analysis, Ikeda isolated glutamic acid as the key compound responsible for this savory sensation. Recognizing its potential in cooking, he neutralized it with sodium, creating monosodium glutamate, a stable, easy-to-use flavor enhancer. Ikeda patented his discovery and founded Ajinomoto, a company that would go on to become a global leader in MSG production and flavor science.

Ikeda not only identified the molecule but also coined the concept of “umami”—a term that translates roughly to “pleasant savory taste” in Japanese. His work laid the foundation for modern taste science, introducing a fifth basic taste that would transform culinary art and food manufacturing worldwide.

Chapter 2: The Chemistry of MSG

MSG is the sodium salt of L-glutamic acid, an amino acid naturally found in many protein-rich foods. Its chemical formula is C₅H₈NO₄Na, and it exists as a crystalline, white powder. When dissolved in water, MSG releases free glutamate ions, which interact directly with taste receptors on the human tongue, creating the umami sensation.

Unlike table salt, which provides a simple salty taste, MSG specifically enhances savory richness, depth, and overall flavor complexity. This molecular specificity allows chefs to boost taste without overwhelming other flavors, making MSG an essential tool in professional kitchens and food science.

MSG is also highly soluble and stable, which means it can be added to liquids, sauces, or dry mixes without losing its flavor-enhancing properties. This makes it versatile for both home cooking and industrial food processing.

Chapter 3: Understanding Umami – The Fifth Taste

Prior to Ikeda’s discovery, humans recognized only four basic tastes: sweet, sour, salty, and bitter. Umami, the fifth taste, is savory, lingering, and deeply satisfying, often described as a “meaty” or “broth-like” flavor. The discovery of umami was revolutionary because it expanded the scientific understanding of taste and showed that human taste perception is far more nuanced than previously thought.

Umami is detected by specialized taste receptors (T1R1/T1R3) on the tongue. When free glutamate ions bind to these receptors, the brain interprets the signal as a rich, savory flavor that enhances the perception of other tastes. This synergy explains why MSG can make vegetables taste meatier, soups taste richer, and sauces taste fuller, even without additional salt or fat.

Chapter 4: Scientific Validation – 1960s and Beyond

While Ikeda discovered umami in 1908, the scientific study of umami advanced significantly in the 1960s. Researchers began conducting controlled taste tests, receptor studies, and chemical analyses to quantify how glutamate affects taste perception.

Key developments included:

- Identification of umami receptors: The T1R1/T1R3 receptor complex in humans was shown to respond specifically to glutamate.

- Flavor synergy studies: Scientists discovered that combining glutamate with nucleotides like inosinate (from meat) or guanylate (from mushrooms) amplifies umami perception far beyond glutamate alone.

- Threshold and safety studies: Researchers determined the concentrations at which MSG enhances flavor without overwhelming the palate.

These studies provided scientific backing for MSG’s use in cooking and food processing, shifting it from anecdotal culinary practice to an evidence-based taste enhancer.

Chapter 5: Culinary Applications – Restaurants, Chefs, and Home Cooking

MSG’s influence on cooking has been profound. In Asian cuisine, it has long been a staple in:

- Japanese kitchens: Ramen broths, miso soup, dashi.

- Chinese cuisine: Stir-fries, sauces, and soups.

- Southeast Asian cooking: Curries, satays, and noodle dishes.

Professional chefs often use MSG to enhance the natural flavors of ingredients rather than dominate them. A pinch in a stock or sauce can make flavors more rounded, richer, and more satisfying. Importantly, MSG allows for lower salt usage while maintaining taste, making it a strategic ingredient for health-conscious cooking.

Restaurants worldwide have adopted MSG strategically. Some fast-food chains use it to maintain consistent flavor in fried foods, soups, and snacks, while fine-dining chefs incorporate MSG to create umami layers in dishes that otherwise rely solely on natural ingredients.

In home kitchens, MSG is typically used sparingly. Knowledgeable cooks may sprinkle a small amount into soups, sauces, or vegetable dishes to replicate the depth of slow-cooked or fermented flavors.

Chapter 6: Natural Sources of Glutamate vs Industrial MSG

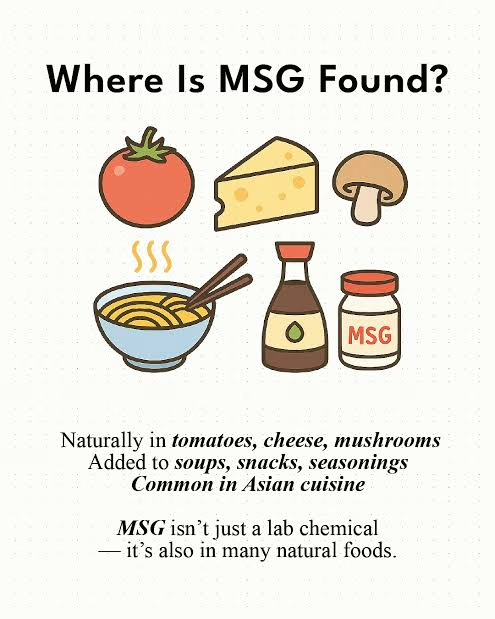

Glutamate occurs naturally in many foods:

- Tomatoes

- Mushrooms

- Cheeses (Parmesan, Roquefort)

- Seaweed, soy sauce, miso

Industrial MSG is produced through fermentation. Starches, sugar beets, sugarcane, or molasses are converted into glutamic acid by bacteria. This acid is neutralized with sodium to produce MSG identical to natural glutamate.

The key advantage of industrial MSG is precision and consistency. It allows chefs and food manufacturers to control flavor accurately, ensuring dishes taste the same every time.

Chapter 7: MSG in the Food Industry

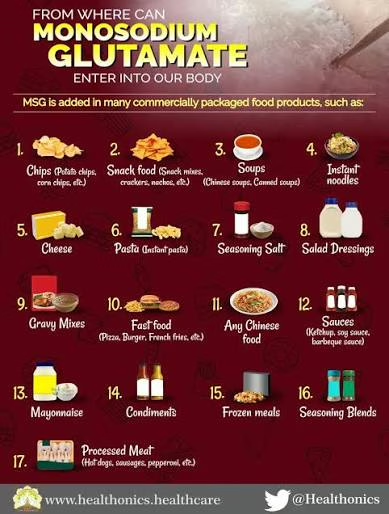

MSG revolutionized the food processing industry:

- Snack foods: Chips, crackers, and seasoning blends rely on MSG for savory flavor.

- Canned and frozen foods: MSG enhances soups, sauces, and ready meals, reducing the need for excess salt.

- Plant-based products: MSG boosts flavor in vegetarian and vegan alternatives, making them taste richer and more satisfying.

Food scientists use MSG not just as a salt substitute but as a flavor amplifier, allowing low-sodium, low-fat, or plant-based foods to achieve full-bodied taste profiles.

Chapter 8: Health, Safety, and Controversies

MSG has faced controversy since the 1960s, particularly regarding “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome”, which reported headaches, flushing, and mild nausea. However, decades of research by the FDA, WHO, and other authorities have consistently found MSG to be safe for the majority of people. Only a small subset may have mild sensitivity.

MSG contains roughly one-third the sodium of table salt, making it an effective tool for reducing overall sodium intake. Doctors and nutritionists often note that MSG can improve adherence to low-sodium diets by enhancing flavor without added salt.

Chapter 9: Chefs’ and Doctors’ Perspectives

Chefs’ opinions:

- MSG is considered a secret weapon in kitchens worldwide.

- It allows chefs to amplify natural flavors without altering texture or color.

- Fine dining kitchens often combine MSG with glutamate-rich ingredients for complex umami layering.

Doctors’ and nutritionists’ opinions:

- MSG is generally recognized as safe (GRAS).

- It can help reduce salt intake, making diets healthier.

- Only a very small percentage of people report mild sensitivity, typically temporary.

Chapter 10: Modern Culinary Science and Molecular Gastronomy

MSG is now part of molecular gastronomy:

- Used to create dishes with precise flavor layering.

- Combined with nucleotides, acids, and fats to enhance taste perception.

- Integral in developing plant-based meats and low-sodium processed foods.

By understanding taste receptors and flavor synergy, chefs can make dishes that feel richer, more indulgent, and satisfying—without relying on excess salt, fat, or sugar.

Chapter 11: Global Acceptance and Cultural Impact

- In Asia, MSG has been a staple for over a century.

- In Western countries, MSG adoption was slower, hindered by early controversies.

- Today, MSG is widely used in both home cooking and industrial food production, thanks to education about its safety and culinary benefits.

Chapter 12: Future Directions

- Plant-based foods: MSG enhances the umami of vegetables, legumes, and grains.

- Low-sodium diets: Strategic use of MSG reduces the need for table salt.

- Flavor science research: Understanding glutamate receptors may allow for even more precise flavor enhancement, creating foods that are healthier and tastier simultaneously.

Chapter 13: Conclusion

Monosodium glutamate is more than a food additive; it is a bridge between science, culture, and culinary art. From Kikunae Ikeda’s discovery in Japan to modern scientific research and professional kitchens, MSG has shaped the flavors we crave, elevating simple ingredients into deeply satisfying dishes.

By unlocking umami, MSG allows chefs, scientists, and home cooks to create balanced, savory, and memorable flavors, proving that science and taste are inseparable allies in the kitchen.

Tomatoes, mushrooms and cheese = MSG!