Franz Xaver Messerschmidt is one of the most enigmatic figures in art history—celebrated, misunderstood, exiled, and finally resurrected in the modern imagination. Best known for his series of unsettling “Character Heads,” Messerschmidt’s work bridges Enlightenment rationalism and expressive proto-modernism, his busts frozen between grotesquerie and revelation. Yet behind the twisted faces lies a story of ambition, displacement, and a mind at odds with the world. This article offers a detailed portrait of the man, his art, and the psychological depths from which it emerged.

Origins and Apprenticeship (1736–1755)

Franz Xaver Messerschmidt was born on February 6, 1736, in the small Bavarian town of Wiesensteig, in what is now southern Germany. He was the sixth of fourteen children born to a modest family—his father was a master tanner. Tragedy struck early in Messerschmidt’s life: his father died when Franz was only nine years old. His mother, left with many children and limited means, sent Franz to live with her brother, Johann Baptist Straub, a prominent sculptor in Munich.

Under Straub’s guidance, Franz was introduced to the world of sculpting. Straub was a master of the late Baroque style, and Messerschmidt quickly demonstrated considerable talent. Later, he moved to Graz, where he worked under another maternal uncle, Philipp Jakob Straub, further honing his technique. These early years provided a firm foundation in figurative sculpture and the dynamic expressiveness of the Baroque idiom.

By the time he was in his late teens, Messerschmidt’s abilities stood out. In 1755, he gained admission to the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, where he studied under Jakob Schletterer. At this stage, Vienna was a major artistic hub in the Habsburg Empire, and Messerschmidt immersed himself in the flourishing aesthetic environment that balanced tradition with the first flickers of Enlightenment thinking.

Early Career in Vienna (1755–1769)

Messerschmidt’s time in Vienna was both formative and professionally successful. While studying at the Academy, he supported himself by working as a sculptor at the imperial arms collection, crafting bronze busts for royal patrons. His commissions for Empress Maria Theresa and Emperor Francis I between 1760 and 1763 marked him as a court favorite. These early works were in keeping with the academic style of the time: formal, stately, and idealized.

A turning point came in 1765 when Messerschmidt traveled to Rome, as many young artists did, to study the classical antiquities and Renaissance masterpieces firsthand. The experience transformed his style. While his earlier work was steeped in the ornamental grandeur of the Baroque, in Rome he encountered the neoclassical ideals of restraint, symmetry, and moral clarity.

Upon returning to Vienna, Messerschmidt began producing works that broke from Baroque expressiveness and embraced neoclassical austerity. His bust of Dr. Gerard van Swieten, for example, is sharply linear and tightly composed, with a clarity reminiscent of Roman Republican sculpture. In 1769, his growing reputation earned him an appointment as an adjunct professor at the Academy of Fine Arts. It seemed he was on a clear path to greater recognition.

But trouble was brewing beneath the surface.

Psychological Decline and Academic Rejection (1769–1774)

Despite his professional achievements, Messerschmidt’s personal behavior began to raise concerns. Colleagues noted signs of instability: obsessive secrecy, increasing isolation, and an almost paranoid intensity. His interpersonal relationships frayed, and his teaching position became untenable. When the leading sculpture professorship became available in 1774, Messerschmidt applied but was rejected. The Academy cited his “confusion in the head” as the reason—a vague but telling phrase that reflected 18th-century notions of mental health.

This rejection shattered him. Humiliated and increasingly alienated from Vienna’s art elite, Messerschmidt saw enemies everywhere. Whether these feelings were symptoms of a deeper psychiatric condition or grounded in the cutthroat politics of the Academy remains an open question. Some scholars believe he may have suffered from schizophrenia, Crohn’s disease, or another chronic illness that affected both body and mind. Others argue that his “madness” was exaggerated or even fabricated by rivals who wished to displace him.

Whatever the case, by the end of 1774, Messerschmidt withdrew from Vienna, effectively ending his academic career.

Exile and Obsession (1775–1777)

Disillusioned, Messerschmidt returned briefly to his hometown of Wiesensteig. But the town offered little opportunity, and the family home could not accommodate him. He drifted toward Munich, seeking new commissions, but found the city unwelcoming. At this time, he began to focus on a radical new project: a series of bizarre, almost grotesque sculptural busts—facial expressions frozen in stone and metal.

By 1777, Messerschmidt relocated permanently to Pressburg (now Bratislava), where his brother Johann Adam Messerschmidt had already settled. There, removed from the demands and constraints of Vienna’s art world, Franz built a studio and embarked on his most iconic work.

The Character Heads (ca. 1770–1783)

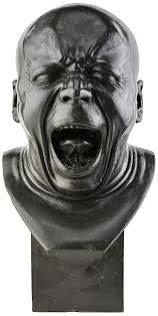

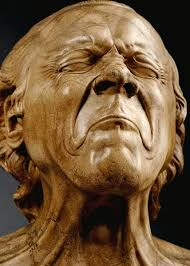

The heart of Messerschmidt’s legacy lies in the series of sculptures now known as the “Character Heads”. Created between roughly 1770 and his death in 1783, these works are unlike anything else from their era. The series originally included 64 busts—though only 49 survive today—each depicting a different extreme facial expression, often bordering on the grotesque or uncanny.

Messerschmidt believed these busts embodied the full range of human physiognomy. Many were self-referential; he used his own face as a model, observing himself in a mirror while inducing expressions through physical manipulation. According to an 18th-century visitor, Friedrich Nicolai, the sculptor would pinch the soft flesh near his ribcage to provoke involuntary grimaces. He then captured these expressions in alabaster, tin-lead alloy, or bronze.

The Spirit of Proportion

During Nicolai’s visit, Messerschmidt revealed that he was haunted by a mystical figure he called the “Spirit of Proportion”—a demon-like entity that tormented him at night. He claimed the Character Heads helped ward off this entity by balancing cosmic energies. This fusion of art, occultism, and self-healing suggests a deeply personal spiritual struggle, blending Enlightenment rationalism with esoteric mysticism.

Selected Works and Their Significance

- The Vexed Man: A tense, tightly coiled bust, with furrowed brow and clenched jaw, that captures frustration in its purest form.

- A Hypocrite and a Slanderer: Slumped and withdrawn, this bust evokes shame and moral failure.

- The Simpleton (Der Schaafkopf): With puffed cheeks and blank stare, this head flirts with the absurd.

- Afflicted with Constipation: A bizarre, exaggerated mask of internal struggle—comedic, tragic, and deeply human.

Though Messerschmidt did not title these works himself, later cataloguers added often humorous names. Behind the laughter, however, lies a deeper resonance: these faces are psychological portraits, capturing something timeless about human emotion and internal conflict.

Legacy of the Character Heads

The busts defied categorization. They were neither classical nor strictly portraiture. Critics of the time were unsure how to interpret them. Some dismissed them as the ravings of a madman. Others recognized their strange brilliance. Messerschmidt never sold the heads during his lifetime. They remained in his studio, a private cosmos of suffering and expression.

After his death, the busts were passed to his brother and eventually exhibited in Vienna in 1793. They attracted significant public interest, and an anonymous biography titled The Peculiar Life History of F.X. Messerschmidt was published in 1794. This was the first time the term “Character Heads” appeared in print.

Death and Obscurity (1783–1900)

Messerschmidt died suddenly in August 1783 at age 47, likely of pneumonia. He was buried in an unmarked grave outside Pressburg. For decades, his work languished in obscurity. His strange heads, considered curiosities or pathological objects, found homes in private collections, often without attribution.

In the 19th century, the busts were misinterpreted through the lens of phrenology and physiognomy, pseudo-sciences that sought to link facial features with moral character. Though discredited today, these theories kept Messerschmidt’s work in circulation, if not in favor.

Rediscovery and Modern Reevaluation (1900–Present)

Interest in Messerschmidt surged again in the early 20th century, particularly among modernist

thinkers and psychoanalysts. Ernst Kris, an early Freud disciple, published a pioneering 1930s study analyzing the heads as expressions of schizophrenia and unconscious conflict. Kris’s essay framed Messerschmidt as a tragic forerunner of modern expressionism.

Later exhibitions in Vienna, Paris, New York, and Berlin recast the Character Heads as masterworks. Critics compared them to Goya, Blake, and even Francis Bacon—artists who revealed psychological and spiritual torment through radical form.

Today, Messerschmidt’s heads are housed in prestigious institutions:

- Belvedere Museum, Vienna

- Getty Museum, Los Angeles

- Louvre, Paris

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Artistic and Psychological Interpretation

The legacy of Messerschmidt’s Character Heads lies in their refusal to be pinned down. Are they:

- Artistic exercises in anatomical study?

- Self-portraits of a tortured soul?

- Mystical protections against demons?

- A visual encyclopedia of human emotion?

In truth, they are all of these things. Their ambiguity is their strength. They confront the viewer with something raw and uncomfortable—yet also compelling and deeply human. In a world increasingly sanitized and curated, Messerschmidt’s work remains visceral, honest, and impossible to ignore.

Conclusion

Franz Xaver Messerschmidt’s life was marked by brilliance, exile, obsession, and misunderstood genius. He moved from the grandeur of imperial commissions to the solitude of inner torment and back into the limelight of critical reevaluation. His Character Heads are among the most arresting sculptural works ever produced, bridging Enlightenment ideals and modern anxieties.

Today, Messerschmidt is no longer seen as a curiosity or a cautionary tale, but as a visionary—one whose silent screams continue to echo across time, asking us not only to observe but to confront ourselves.

Like reading it? Stay tuned for more!!