1. Origins: A Genius Trio Forms a Drawing Legacy

From Revolution to Art School

Porfiri Krylov (b. 1902), Mikhail Kupriyanov (b. 1903), and Nikolai Sokolov (b. 1903) each grew up during Imperial Russia and came of age during the 1917 Revolution’s turbulence (Lambiek). In the early 1920s, they met as students at VKhUTEMAS, Moscow’s avant-garde art institute—a melting pot of art, design, and revolutionary ideas (Lambiek). By 1924, inspired by camaraderie and shared vision, they began collaborating.

Birth of a Name

Initially signing as “KuKry” (Kupriyanov + Krylov), they welcomed Sokolov and added “Niks” to become KuKryNiksy, a playful, distinctive collective pseudonym that echoed their commitment to unified creative work (GW2RU).

2. Early Work: Caricature, Theater, and Illustration

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, the trio gained traction working for satirical magazines like Krokodil, Krokodil, Smekhach, and newspapers including Pravda and Komsomolskaya Pravda (archive.artic.edu). They also designed sets and costumes—most notably for Mayakovsky’s play The Bedbug—garnering acclaim and a gold medal at the 1937 Paris International Exhibition (archive.artic.edu).

Their early work ranged from playful cultural caricatures to editorial cartoons, book illustrations for Russian and world classics, and even decorative porcelain portraits of personalities like Stanislavsky and Prokofiev .

3. The Rise of Political Satire

Anti-Fascist Sentiment on Paper

As Fascism swept across Europe in the 1930s, Kukryniksy sharpened their focus. Through grotesque exaggeration and vivid metaphor, they painted Mussolini, Franco, Hitler, and key Nazi figures in scathing satirical portraits that spread through Soviet media and exhibitions (Wikipedia).

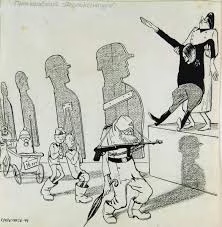

Inventive Visual Language

Their satire relied on turning powerful figures into absurd caricatures—mimicking snakes, crows, or human-animal hybrids—and applying hyperbole to transform fear into ridicule. This visual strategy both engaged and educated readers about the political climate beyond their borders .

4. World War II: TASS Windows and Propaganda Posters

In 1941, when Nazi Germany invaded the USSR, Kukryniksy sprang into action. Within two days, their first war poster “Ruthlessly defeat and destroy the enemy!” was plastered across Soviet city streets, galvanizing resolve and unity (GW2RU).

TASS Windows

They joined the TASS Windows program—giant poster-displays akin to propaganda bulletins created by the Soviet news agency—to churn out 74 posters over four years. These images combined up-to-the-minute political commentary with bold graphics designed to both inspire Soviets and demoralize invaders (library.brown.edu).

Leaflets and Frontline Influence

Beyond posters, they crafted leaflets dropped behind enemy lines, urging German soldiers to surrender. Their impact became so renowned that Hitler reportedly placed them on his kill list .

5. After the War: Trial Sketches and Cold War Caricatures

Nuremberg Drawings

In a unique turn, they were invited as journalists to the Nuremberg Trials. Their sketches of Nazi leaders on trial were published globally and helped shape the visual narrative of justice. Later, they commemorated the event in a sweeping canvas titled “Accusation. The Nuremberg Trials” (Russia Beyond).

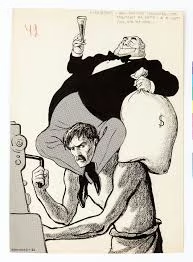

Cold War Themes

In the post-war era, their subjects shifted to Western powers. A series of Cold War drawings, stretching from the 1950s through the 1980s, satirized NATO, U.S. policies, nuclear escalation, and UN politics—sometimes with biting wit, other times toeing the line of official Soviet messaging (Военное обозрение).

6. Working Together… and Apart

A Seamless Collaboration

For over sixty years, they worked physically together—sometimes residing in the same Moscow building—and never quarreled. Their process: each sketched ideas independently, then pooled the best into a unified piece engraved with the name “Kukryniksy” (GW2RU).

Individual Endeavors

Outside politics, they pursued solo work: landscapes, portraits, and more realistic compositions, signed under their real names to separate them from their collective political identity .

7. Honors, Exhibitions, and Legacy

Awards & Recognition

Their talent was officially recognized: five Stalin Prizes (1942, 1947, 1949, 1950, 1951), the Lenin Prize (1965), and the State Prize of the USSR (1975). They were inducted into the Academy of Fine Arts, named People’s Artists of the USSR, and awarded the title Heroes of Socialist Labor (archive.artic.edu).

Exhibitions Worldwide

International exhibitions—from Vienna to Chicago—have revisited their work, showcasing its historical value and its unexpected artistry beyond propaganda. Critics now point out their ties to visual traditions of earlier European art and recognize existential undercurrents in their bold compositions .

Collections Today

Their works are held in major institutions like the Art Institute of Chicago, MoMA, Russian Museum, Tretyakov Gallery, and numerous private collections, including the Mamontov Collection—the world’s largest private archive of their art .

8. Why Kukryniksy Still Matters

Political Art That Transcends Its Era

Their caricatures may have served propaganda, but their clever satire and powerful visuals speak universally. They demonstrated how art can turn fearsome figures into absurd characters—eroding authority with humor.

Collaboration as Art

Few artistic collectives have sustained for six decades without discord. Their partnership embodies trust, shared voice, and creative synergy that’s rare in any era—an inspiring model for visual collaboration.

Beyond Soviet Icons

While shaped by Soviet ideology, their visual impact and imaginative compositions lift them beyond their politics. Modern viewers—and critics—appreciate their designs for their artistic innovation as much as historical importance .

9. In Their Own Words: A Daily Routine

- Sketch, share, refine: Each artist offered drafts; only the best ideas merged.

- Immediate production: When war broke out, they turned sketches into street posters in days.

- Versatility: They moved seamlessly between satire, book illustration, poster design, theater, and easel painting.

- Living in concert: Their lives were as collective as their art—studio, home, and mission interwoven.

10. Notable Works & Series

Here are a few celebrated pieces and themes, embodying their range:

- “Ruthlessly defeat the enemy!” – First wartime poster, June 1941.

- Anti-Nazi caricatures, featuring Goebbels, Göring, Himmler.

- TASS Windows series – 70+ posters during WWII, combining maps, caricatures, and bold slogans.

- “Accusation. The Nuremberg Trials” – Epic postwar canvas depicting Nazi defendants.

- Cold War images – from “Trustworthy Statue of Liberty” (1953) to “Pentagoning everyone” (1977).

- Children’s books & fairy tales – illustrated with wit and tenderness (e.g. Saltykov-Shchedrin).

- Portraits, landscapes, still lifes – individual works showing personal style.

Final Reflection

To audiences outside the Soviet sphere, Kukryniksy may seem a paradox: propaganda artists revered for satire. Yet their collaborative genius, political audacity, and graphic flair remain compelling instantly. They remind us that cartoon art can be serious history—and that art born under ideology can also transcend it.

Their legacy persists beyond ideology: a vivid testament to collaborative creativity and the power of wit and imagery in shaping ideas.