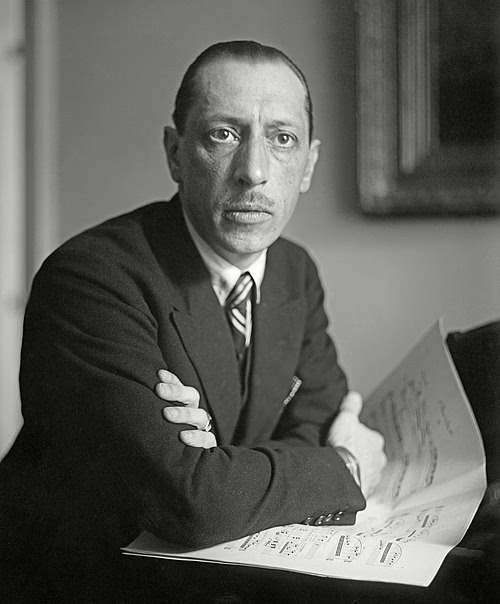

Born to a musical family in Saint Petersburg, Russia, Stravinsky grew up taking piano and music theory lessons. While studying law at the University of Saint Petersburg, he met Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and studied music under him until the latter’s death in 1908. Stravinsky met the impresario Sergei Diaghilev soon after, who commissioned the composer to write three ballets for the Ballets Russes‘s Paris seasons: The Firebird (1910), Petrushka (1911), and The Rite of Spring (1913), the last of which caused a near-riot at the premiere due to its avant-garde nature and later changed the way composers understood rhythmic structure.

Stravinsky’s compositional career is often divided into three main periods: his Russian period (1913–1920), his neoclassical period (1920–1951), and his serial period (1954–1968). During his Russian period, Stravinsky was heavily influenced by Russian styles and folklore. Works such as Renard (1916) and Les noces (1923) drew upon Russian folk poetry, while compositions like L’Histoire du soldat (1918) integrated these folk elements with popular musical forms, including the tango, waltz, ragtime, and chorale. His neoclassical period exhibited themes and techniques from the classical period, like the use of the sonata form in his Octet (1923) and use of Greek mythological themes in works including Apollon musagète (1927), Oedipus rex (1927), and Persephone (1935). In his serial period, Stravinsky turned towards compositional techniques from the Second Viennese School like Arnold Schoenberg‘s twelve-tone technique. In Memoriam Dylan Thomas (1954) was the first of his compositions to be fully based on the technique, and Canticum Sacrum (1956) was his first to be based on a tone row. Stravinsky’s last major work was the Requiem Canticles (1966), which was performed at his funeral.

While many supporters were confused by Stravinsky’s constant stylistic changes, later writers recognized his versatile language as important in the development of modernist music. Stravinsky’s revolutionary ideas influenced composers as diverse as Aaron Copland, Philip Glass, Béla Bartók, and Pierre Boulez, who were all challenged to innovate music in areas beyond tonality, especially rhythm and musical form. In 1998, Time magazine listed Stravinsky as one of the 100 most influential people of the century. Stravinsky died of pulmonary edema on 6 April 1971 in New York City, having left six memoirs written with his friend and assistant Robert Craft, as well as an earlier autobiography and a series of lectures. Claude Debussy credited Stravinsky with having “enlarged the boundaries of the permissible” in music.

Early life in Russia, 1882–1901

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky was born in Oranienbaum, Russia—a town later renamed Lomonosov, about thirty miles (fifty kilometers) west of Saint Petersburg—on 17 June [O.S. 5 June] 1882. His mother, Anna Kirillovna Stravinskaya] (née Kholodovskaya), was an amateur singer and pianist from an established family of landowners. His father, Fyodor Ignatyevich Stravinsky, was a famous bass at the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg, descended from a line of Polish landowners. The name “Stravinsky” is of Polish origin, deriving from the Strava river in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The family was originally called “Soulima-Stravinsky”, bearing the Soulima arms, but “Soulima” was dropped after Russia’s annexation during the partitions of Poland.

Oranienbaum, the composer’s birthplace, was where his family vacationed during summers; their primary residence was an apartment along the Kryukov Canal in central Saint Petersburg, near the Mariinsky Theatre. Stravinsky was baptized hours after birth and joined to the Russian Orthodox Church in St. Nicholas Cathedral. Constantly in fear of his short-tempered father and indifferent towards his mother, Igor lived there for the first 27 years of his life with three siblings: Roman and Yury, his older siblings who irritated him immensely, and Gury, his close younger brother with whom he said he found “the love and understanding denied us by our parents”. Igor was educated by the family’s governess until age eleven, when he began attending the Second Saint Petersburg Gymnasium, a school he recalled hating because he had few friends.

From age nine, Stravinsky studied privately with a piano teacher. He later wrote that his parents saw no musical talent in him due to his lack of technical skills; the young pianist frequently improvised instead of practicing assigned pieces. Stravinsky’s excellent sight-reading skill prompted him to frequently read vocal scores from his father’s vast personal library. At around age ten, he began regularly attending performances at the Mariinsky Theatre, where he was introduced to Russian repertoire as well as Italian and French opera; by sixteen, he attended rehearsals at the theater five or six days a week. By age fourteen, Stravinsky had mastered the solo part of Mendelssohn‘s Piano Concerto No. 1, and at age fifteen, he transcribed for solo piano a string quartet by Alexander Glazunov.

Despite his musical passion and ability, Stravinsky’s parents expected him to study law at the University of Saint Petersburg, and he enrolled there in 1901. However, according to his own account, he was a bad student and attended few of the optional lectures. In exchange for agreeing to attend law school, his parents allowed for lessons in harmony and counterpoint.[24] At university, Stravinsky befriended Vladimir Rimsky-Korsakov, son of the leading Russian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. During summer vacation of 1902, Stravinsky traveled with Vladimir Rimsky-Korsakov to Heidelberg – where the latter’s family was staying – bringing a portfolio of pieces to demonstrate to Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. While the elder composer was not stunned, he was impressed enough to insist that Stravinsky continue lessons but advised against him entering the Saint Petersburg Conservatory due to its rigorous environment. Importantly, Rimsky-Korsakov agreed personally to advise Stravinsky on his compositions.

After Stravinsky’s father died in 1902 and the young composer became more independent, he became increasingly involved in Rimsky-Korsakov’s circle of artists. His first major task from his new teacher was the four-movement Piano Sonata in F-sharp minor in the style of Glazunov and Tchaikovsky – he paused temporarily to write a cantata for Rimsky-Korsakov’s 60th birthday celebration, which the elder composer described as “not bad”. Soon after finishing the sonata, the student began his large-scale Symphony in E-flat,[e] the first draft of which he finished in 1905. That year, the dedicatee of the Piano Sonata, Nikolay Richter, performed it at a recital hosted by the Rimsky-Korsakovs, marking the first public premiere of a Stravinsky piece.

After the events of Bloody Sunday in January 1905 caused the university to close, Stravinsky was not able to take his final exams, resulting in his graduation with a half-diploma. As he began spending more time in Rimsky-Korsakov’s circle of artists, the young composer became increasingly cramped in the stylistically conservative atmosphere: modern music was questioned, and concerts of contemporary music were looked down upon. The group occasionally attended chamber concerts oriented to modern music, and while Rimsky-Korsakov and his colleague Anatoly Lyadov hated attending, Stravinsky remembered the concerts as intriguing and intellectually stimulating, being the first place he was exposed to French composers like Franck, Dukas, Fauré, and Debussy. Nevertheless, Stravinsky remained loyal to Rimsky-Korsakov – the musicologist Eric Walter White suspected that the composer believed compliance with Rimsky-Korsakov was necessary to succeed in the Russian music world. Stravinsky later wrote that his teachers’ musical conservatism was justified, and helped him build the foundation that would become the base of his style.

First marriage

In August 1905, Stravinsky announced his engagement to Yekaterina Nosenko, his first cousin whom he had met in 1890 during a family trip. He later recalled:

From our first hour together we both seemed to realize that we would one day marry—or so we told each other later. Perhaps we were always more like brother and sister. I was a deeply lonely child and I wanted a sister of my own. Catherine, who was my first cousin, came into my life as a kind of long-wanted sister … We were from then until her death extremely close, and closer than lovers sometimes are, for mere lovers may be strangers though they live and love together all their lives … Catherine was my dearest friend and playmate … until we grew into our marriage.

The two had grown close during family trips, encouraging each other’s interest in painting and drawing, swimming together often, going on wild raspberry picks, helping build a tennis court, playing piano duet music, and later organizing group readings with their other cousins of books and political tracts from Fyodor Stravinsky’s personal library. In July 1901, Stravinsky expressed infatuation with Lyudmila Kuxina, Nosenko’s best friend, but after the self-described “summer romance” had ended, Nosenko and Stravinsky’s relationship began developing into a furtive romance. Between their intermittent family visits, Nosenko studied painting at the Académie Colarossi in Paris. The two married on 24 January 1906, at the Church of the Annunciation five miles (eight kilometers) north of Saint Petersburg – because marriage between first cousins was banned, they procured a priest who did not ask their identities, and the only guests present were Rimsky-Korsakov’s sons.[38] The couple soon had two children: Théodore, born in 1907, and Ludmila, born the following year.

After finishing the many revisions of the Symphony in E-flat in 1907, Stravinsky wrote Faun and Shepherdess, a setting of three Pushkin poems for mezzo-soprano and orchestra.[30] Rimsky-Korsakov organized the first public premiere of his student’s work with the Imperial Court Orchestra in April 1907, programming the Symphony in E-flat and Faun and Shepherdess.[24][40] In 1908, he sent the score of Feu d’artifice to Rimsky-Korsakov. It was returned with the note: “Not delivered on account of death of addressee.” Rimsky-Korsakov’s death in June 1908 caused Stravinsky deep mourning, and he later recalled that Funeral Song, which he composed in memory of his teacher, was “the best of my works before The Firebird“.

While composing The Firebird, Stravinsky conceived an idea for a work about what he called “a solemn pagan rite: sage elders, seated in a circle, watched a young girl dance herself to death”. He immediately shared the idea with Nicholas Roerich, a friend and painter of pagan subjects. When Stravinsky told Diaghilev about the idea, the impresario excitedly agreed to commission the work. After the premiere of Petrushka, Stravinsky settled at his family’s residence in Ustilug and fleshed out the details of the ballet with Roerich, later finishing the work in Clarens, Switzerland. The result was The Rite of Spring (Le sacre du printemps), which depicted pagan rituals in Slavonic tribes and used many avant-garde techniques, including uneven rhythms and meters, superimposed harmonies, atonality, and extensive instrumentation. With radical choreography by the young Vaslav Nijinsky, the ballet’s experimental nature caused a near-riot at its premiere at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées on 29 May 1913.

France, 1920–1939

Turn towards neoclassicism

After the war ended, Stravinsky decided that his residence in Switzerland was too far from Europe’s musical activity, and briefly moved his family to Carantec, France. In September 1920, they relocated to the home of Coco Chanel, an associate of Diaghilev’s, where Stravinsky composed his early neoclassical work the Symphonies of Wind Instruments. After his relationship with Chanel developed into an affair, Stravinsky relocated his family to the white émigré-hub Biarritz in May 1921, partly due to the presence of his other lover Vera de Bosset. At the time, de Bosset was married to the former Ballet Russes stage designer Serge Sudeikin, though de Bosset later divorced Sudeikin to marry Stravinsky. Though Yekaterina Stravinsky became aware of her husband’s infidelity, the Stravinskys never divorced, likely due to the composer’s refusal to separate.

In 1921, Stravinsky signed a contract with the player piano company Pleyel to create piano roll arrangements of his music. He received a studio at their factory on the Rue Rochechouart, where he reorchestrated Les noces for a small ensemble including player piano. The composer transcribed many of his major works for the mechanical pianos, and the Pleyel premises remained his Paris base until 1933, even after the player piano had been largely supplanted by electrical gramophone recording. Stravinsky signed another contract in 1924, this time with the Aeolian Company in London, producing rolls that included comments about the work by Stravinsky that were engraved into the rolls. He stopped working with player pianos in 1930 when the Aeolian Company’s London branch was dissolved.

The interest in Pushkin shared by Stravinsky and Diaghilev led to Mavra, a comic opera begun in 1921 that exhibited the composer’s rejection of Rimsky-Korsakov’s style and his turn towards classic Russian operatists like Tchaikovsky, Glinka, and Dargomyzhsky.[92][97] Yet, after the 1922 premiere, the work’s tame nature – compared to the innovative music Stravinsky had come to be known for – disappointed critics. In 1923, Stravinsky finished orchestrating Les noces, settling on a percussion ensemble including four pianos. The Ballets Russes staged the ballet-cantata that June, and although it initially received moderate reviews, the London production received a flurry of critical attacks, leading the writer H. G. Wells to publish an open letter in support of the work.[101][102] During this period, Stravinsky expanded his involvement in conducting and piano performance. He conducted the premiere of his Octet in 1923 and served as the soloist for the premiere of his Piano Concerto in 1924. Following its debut, he embarked on a tour, performing the concerto in over 40 concerts.

Religious crisis and international touring

The Stravinsky family moved again in September 1924 to Nice, France. The composer’s schedule was divided between spending time with his family in Nice, performing in Paris, and touring other locations, often accompanied by de Bosset. At this time, Stravinsky was going through a spiritual crisis onset by meeting Father Nicolas, a priest near his new home. He had abandoned the Russian Orthodox Church during his teenage years, but after meeting Father Nicolas in 1926 and reconnecting with his faith, he began regularly attending services. From then until moving to the United States,[o] Stravinsky diligently attended church, participated in charity work, and studied religious texts. The composer later wrote that he was contacted by God at a service at the Basilica of Saint Anthony of Padua, leading him to write his first religious composition, the Pater Noster for a cappella choir.

In 1925, Stravinsky asked the French writer and artist Jean Cocteau to write the libretto for an operatic setting of Sophocles‘ tragedy Oedipus Rex in Latin.[110] The May 1927 premiere of his opera-oratorio Oedipus rex was staged as a concert performance since there was too little time and money to present it as a full opera, and Stravinsky attributed the work’s critical failure to its programming between two glittery ballets. Furthermore, the influence from Russian Orthodox vocal music and 18th-century composers like Handel was not well received in the press after the May 1927 premiere; neoclassicism was not popular with Parisian critics, and Stravinsky had to publicly assert that his music was not part of the movement. This reception from critics was not improved by Stravinsky’s next ballet, Apollon musagète, which depicted the birth and apotheosis of Apollo using an 18th-century ballet de cour musical style. George Balanchine choreographed the premiere, beginning decades of collaborations between Stravinsky and the choreographer. Nevertheless, some critics found it to be a turning point in Stravinsky’s neoclassical music, describing it as a pure work that blended neoclassical ideas with modern methods of composition.

A new commission for a ballet from Ida Rubinstein in 1928 led Stravinsky again to Tchaikovsky. Basing the music on romantic ballets like Swan Lake and borrowing many themes from Tchaikovsky, Stravinsky wrote The Fairy’s Kiss with Hans Christian Andersen‘s tale The Ice-Maiden as the subject. The November 1928 premiere was not well-received, likely due to the disconnect between each of the ballet’s sections and the mediocre choreography, of which Stravinsky disapproved. Diaghilev’s fury with Stravinsky for accepting a ballet commission from someone else caused an intense feud between the two, one that lasted until the impresario’s death in August 1929. Most of that year was spent composing a new solo piano work, the Capriccio, and touring across Europe to conduct and perform piano; the Capriccio’s success after the December 1929 premiere caused a flurry of performance requests from many orchestras. A commission from the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1930 for a symphonic work led Stravinsky back to Latin texts, this time from the book of Psalms.[124] Between touring concerts, he composed the choral Symphony of Psalms, a deeply religious work that premiered in December of that year.

Work with Dushki

While touring in Germany, Stravinsky visited his publisher’s home and met the violinist Samuel Dushkin, who convinced him to compose the Violin Concerto with Dushkin’s help on the solo part. Impressed by Dushkin’s virtuosic ability and understanding of music, the composer wrote more music for violin and piano and rearranged some of his earlier music to be performed alongside the Concerto while on tour until 1933. That year, Stravinsky received another ballet commission from Ida Rubenstein for a setting of a poem by André Gide. The resulting melodrama Perséphone only received three performances in 1934 due to its lukewarm reception, and Stravinsky’s disdain towards the work was evident in his later suggestion that the library was rewritten. In June of that year, Stravinsky became a naturalized French citizen, protecting all his future works under copyright in France and the United States. His family subsequently moved to an apartment on the Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré in Paris, where he began writing a two-volume autobiography with the help of Walter Nouvel, published in 1935 and 1936 as Chroniques de ma vie.

After the short run of Perséphone, Stravinsky embarked on a successful three-month tour of the United States with Dushkin; he visited South America for the first time the following year. The composer’s son Soulima was an excellent pianist, having performed the Capriccio in concert with his father conducting. Continuing a line of solo piano works, the elder Stravinsky composed the Concerto for Two Pianos to be performed by them both, and they toured the work through 1936. Around this time came three American-commissioned works: the ballet Jeu de cartes for Balanchine, the Brandenburg Concerto-like work Dumbarton Oaks, and the lamenting Symphony in C for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra‘s 50th anniversary. Stravinsky’s last years in France from late 1938 to 1939 were marked by the deaths of his eldest daughter, his wife, and his mother, the former two from tuberculosis. In addition, the increasingly hostile criticism of his music in major publications[q] and failed run for a seat at the Institut de France further dissociated him from France, and shortly after the beginning of World War II in September 1939 he moved to the United States.

United States, 1939–1971

Adjustment to the United States and commercial works

Upon arriving in the United States, Stravinsky resided with Edward W. Forbes, the director of the Charles Eliot Norton Lectures series at Harvard University. The composer was contracted to deliver six lectures for the series, beginning in October 1939 and ending in April 1940.[143][144][145] The lectures, written with assistance from Pyotr Suvchinsky and Alexis Roland-Manuel, were published in French under the title Poétique musicale (Poetics of Music) in 1941, with an English translation following in 1947. Between lectures, Stravinsky finished the Symphony in C and toured across the country, meeting de Bosset upon her arrival in New York. Stravinsky and de Bosset finally married on 9 March 1940 in Bedford, Massachusetts. After the completion of his lecture series, the couple moved to Los Angeles, where they applied for American naturalization.

Money became scarce as the war stopped the composer from receiving European royalties, making him take up numerous conducting engagements and compose commercial works for the entertainment industry, including the Scherzo à la russe for Paul Whiteman and the Scènes de ballet for a Broadway revue. Some discarded film music made it into larger works, as with the war-inspired Symphony in Three Movements, the middle movement of which used music from an unused score for The Song of Bernadette (1943). The couple’s poor English led to the formation of a predominantly European social circle and home life: the estate staff consisted of mostly Russians, and frequent guests included musicians Joseph Szigeti, Arthur Rubinstein, and Sergei Rachmaninoff. However, Stravinsky eventually joined popular Hollywood circles, attending parties with celebrities and becoming closely acquainted with European authors Aldous Huxley, W. H. Auden, Christopher Isherwood, and Dylan Thomas.

In 1945, Stravinsky received American citizenship and subsequently signed a contract with British publishing house Boosey & Hawkes, who agreed to publish all his future works. Additionally, he revised many of his older works and had Boosey & Hawkes publish the new editions to re-copyright his older works. Around the 1948 premiere of another Balanchine collaboration, the ballet Orpheus, the composer met the young conductor Robert Craft in New York; Craft had asked Stravinsky to explain the revision of the Symphonies of Wind Instruments for an upcoming concert. The two quickly became friends and Stravinsky invited Craft to Los Angeles; the young conductor soon became Stravinsky’s assistant, collaborator, and amanuensis until the composer’s death.

Turn towards serialism

As Stravinsky became more familiar with English, he developed the idea to write an English-language opera based on a series of paintings by 18th-century artist William Hogarth titled The Rake’s Progress. The composer joined Auden to write the libretto in November 1947; American writer Chester Kallman was later brought in to assist Auden. Stravinsky finished the opera of the same name in 1951, and despite its widespread performances and success, the composer was dismayed to find that his newer music did not captivate young composers. Craft had introduced Stravinsky to the serial music of the Second Viennese School shortly after The Rake’s Progress premiered, and the opera’s composer began studying and listening to the music of Anton Webern and Arnold Schoenberg.

During the 1950s, Stravinsky continued touring extensively across the world, occasionally returning to Los Angeles to compose. In 1953, he agreed to compose a new opera with a libretto by Dylan Thomas, but development on the project came to a sudden end following Thomas’s death in November of that year. Stravinsky completed In Memoriam Dylan Thomas, his first work fully based on the serial twelve-tone technique, the following year.[162][166] The 1956 cantata Canticum Sacrum premiered at the International Festival of Contemporary Music in Venice, inspiring Norddeutscher Rundfunk to commission the musical setting Threni in 1957. With the Balanchine ballet Agon, Stravinsky fused neoclassical themes with the twelve-tone technique, and Threni showed his full shift towards use of tone rows.[162] In 1959, Craft interviewed Stravinsky for an article titled Answers to 35 Questions, in which the composer sought to correct myths surrounding him and discuss his relationships with other artists. The article was later expanded into a book, and over the next four years, three more interview-style books were published.

Continued international tours brought Stravinsky to Washington, D.C. in January 1962, where he attended a dinner at the White House with then-President John F. Kennedy in honor of the composer’s 80th birthday. Although it was largely an anti-Soviet political stunt, Stravinsky remembered the event fondly, composing the Elegy for J.F.K. after the president’s assassination a year later. In September 1962, he returned to Russia for the first time since 1914, accepting an invitation from the Union of Soviet Composers to conduct six performances in Moscow and Leningrad. After the success of The Firebird and The Rite of Spring in the 1910s, Stravinsky’s music was respected and frequently performed in the Soviet Union, influencing young Soviet composers at the time like Dmitri Shostakovich. However, after Stalin began consolidating power in the early 1930s, Stravinsky’s music nearly vanished and was formally banned in 1948. A new interest in his works was born during the Khrushchev Thaw, partly due to the composer’s 1962 visit. During his three-week visit he met with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev and several leading Soviet composers, including Shostakovich and Aram Khachaturian. Stravinsky did not return to Los Angeles until December 1962 after eight months of almost continual traveling.

Final works and death

Stravinsky revisited biblical themes for many of his later works, notably in the 1961 chamber cantata A Sermon, a Narrative and a Prayer, the 1962 musical television production The Flood, the 1963 Hebrew cantata Abraham and Isaac, and the 1966 Requiem Canticles, the last of which was his final major composition. Between tours, the composer worked relentlessly to devise new tone rows, even working on toilet paper from airplane lavatories. The intense touring schedule began taking a toll on the elderly composer; January 1967 marked his last recording session, and his final concert came the following May. An obviously very frail Stravinsky made his final public conducting appearance on May 17, 1967 at Massey Hall in Toronto, when he led the Toronto Symphony Orchestra in a performance of his Pulcinella Suite.

After spending the autumn of 1967 in the hospital due to bleeding stomach ulcers and thrombosis, Stravinsky returned to domestic touring in 1968 (only appearing as an audience member) but stopped composing due to his gradual decline in physical health.

In his final years, the Stravinskys and Craft moved to New York to be closer to medical care, and the composer’s travel was limited to visiting family in Europe. Soon after being discharged from Lenox Hill Hospital after contracting pulmonary edema, Stravinsky moved with his wife to a new apartment on Fifth Avenue. The composer died there on 6 April 1971 at the age of 88. A funeral service was held three days later at the Frank E. Campbell Funeral Chapel.[186] After a service at Santi Giovanni e Paolo with a performance of the Requiem Canticles conducted by Craft, Stravinsky was buried on the cemetery island of San Michele in Venice, several meters from the tomb of Sergei Diaghilev.