The Quiet Power of Sushi

There are few foods in the world as deceptively simple, as deeply revered, and as profoundly misunderstood as sushi. A morsel of vinegared rice paired with raw fish, served with elegance and silence, can command reverence, ignite controversy, and even change a life. For some, it’s a sacred ritual; for others, a lunchtime snack. For Japan, sushi is more than a dish—it is a national treasure, an emblem of craftsmanship, philosophy, and heritage. This article is a journey through the true history, culture, traditions, evolution, and global presence of sushi. It’s a tribute to those who created it, who preserve it, and who dare to reinterpret it.

1. The Origins of Sushi

The Etymology: From Vinegar and Rice to Global Art

The word sushi doesn’t mean “raw fish”—a misconception that plagues the dish globally. Instead, it comes from an older Japanese term, su-meshi (vinegared rice). The core of sushi is not fish, but rice—perfectly prepared, subtly seasoned, and served at the right temperature. The term evolved over centuries, influenced by Chinese preservation techniques and transformed into the Japanese culinary art we know today.

Birth in Southeast Asia: Narezushi and Fermentation

Sushi’s earliest ancestor emerged in Southeast Asia over 2,000 years ago. It began as a method to preserve fish: narezushi, where gutted fish was packed in fermented rice to slow decomposition. This technique traveled to China and later reached Japan around the 8th century. Japanese chefs eventually began discarding the rice and eating only the fermented fish, before discovering that the rice itself could be seasoned and consumed.

2. The Evolution of Sushi in Japan

From Narezushi to Hayazushi

In the Muromachi period (1336–1573), sushi saw a radical transformation. The Japanese started using vinegar to replicate the sour taste of fermentation, eliminating the need for long wait times. This led to hayazushi—“fast sushi”—a precursor to the fresh, quick-service sushi of today.

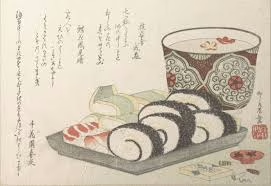

The Edo Period and the Birth of Nigiri

By the Edo period (1603–1868), Tokyo (then Edo) was bustling, and street food boomed. Enter nigirizushi, the modern form of sushi: a small hand-pressed block of vinegared rice topped with raw or cooked fish, created by Hanaya Yohei around 1824. It was fast, fresh, and portable—perfect for Edo’s working class.

3. The First Masters and Historic Restaurants

Hanaya Yohei and the Nigiri Revolution

Hanaya Yohei is considered the father of modern sushi. He opened a street stall near the Sumida River and began selling nigiri using freshly caught fish from the bay. His sushi was affordable, flavorful, and elegant—drawing attention from commoners and nobles alike.

The Oldest Sushi Establishments

Restaurants like Yoshino Sushi in Tokyo, dating back to 1879, stand as testaments to sushi’s enduring prestige. These establishments shaped the codes and aesthetics of sushi, setting the stage for the traditional sushi-ya format.

Apprenticeship and Hierarchy

Becoming an itamae (sushi chef) is not simply a job—it’s a spiritual journey. Apprentices spend years washing rice, cleaning the floor, and observing the master before they even touch a knife. The discipline, patience, and humility involved are unmatched in most culinary arts.

4. Traditions, Codes, and Restrictions

The Path to Perfection

Tradition rules sushi. From the angle of a blade to the moisture of the rice, everything matters. Ingredients must be seasonal and local. Fish must be sliced according to its texture and fat content. Even wasabi placement depends on the fish’s profile.

Restrictions That Guard Purity

- No perfumes or strong smells in sushi bars

- No tipping in many traditional establishments

- No soy sauce dunking—chefs may pre-season your sushi

- Omakase (chef’s choice) is a sign of trust and surrender

5. The Sacred Craft: Worship of Sushi Masters

The Mythology of the Itamae

In Japan, elite sushi masters are treated like living gods. Their restaurants are shrines. Their hands, tools of the divine. Jiro Ono, of Sukiyabashi Jiro, became world-famous after the documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi. His 10-seat Tokyo restaurant once held three Michelin stars and a months-long waiting list. Even former U.S. President Obama sought a seat at his counter.

The Dream of Dining at the Altar

For sushi lovers, dining at a traditional omakase restaurant in Japan is a pilgrimage. These places are quiet, respectful, and demanding. A meal can cost hundreds of dollars, last over two hours, and include just ten pieces of sushi—each served in deliberate order, perfectly timed.

6. The Westernization of Sushi

The California Roll Revolution

As sushi spread to the West in the 20th century, it encountered new ingredients and palates. The California Roll—created by Japanese chefs in Los Angeles—replaced raw fish with avocado and imitation crab. It was a huge hit, and marked the beginning of “fusion sushi.”

Cream Cheese, Mango, and Deep-Fried Rolls

What followed was culinary chaos—or genius, depending on perspective. Spicy tuna rolls, Philadelphia rolls, sushi burritos, tempura-fried maki—these Frankenstein creations redefined sushi for a Western audience but alarmed Japanese traditionalists.

7. East Meets West: A New Sushi Universe

The Great Sushi Schism

Today, sushi exists in two worlds: the sacred and the secular. In one, the rice is studied for years. In the other, it’s microwaved. Yet both worlds have merit. Western sushi made sushi accessible, fun, and customizable—reaching millions who might never eat raw fish otherwise.

Michelin Stars and Fusion Fame

Chefs like Nobu Matsuhisa and Masaharu Morimoto gained global fame by blending Japanese techniques with Peruvian, American, and French styles. Their high-end sushi empires cater to celebrities and diplomats, blurring the line between authenticity and innovation.

8. Techniques and Styles

Forms of Sushi

- Nigiri: Hand-pressed rice with fish

- Maki: Rolled sushi, often in seaweed

- Temaki: Hand-rolled cone-shaped sushi

- Chirashi: Scattered sushi bowl

- Gunkan: Battleship-style with loose toppings

- Oshizushi: Pressed sushi, from Osaka

Knife Skills and Rice Mastery

Sushi chefs master yanagiba knives, slicing fish in precise strokes to preserve integrity and texture. Rice must be slightly warm, not sticky, and seasoned with perfect vinegar balance. Hands must be clean and moist but never wet.

Subtle Language of the Craft

The way sushi is handed over, the nod from the chef, the spacing between courses—these unspoken signals form the language of sushi service, deepening the connection between chef and guest.

9. Competitions, Rituals, and Events

World Sushi Cup Japan

Every year, chefs gather to compete in the World Sushi Cup, showcasing their skills under pressure, judged by master itamae. It’s a fierce display of speed, artistry, and precision.

Local and Global Festivals

From the Tsukiji Fish Market Festival in Tokyo to Sushi Fest in Toronto and Paris, sushi is celebrated with enthusiasm. These events honor both the ancient traditions and bold innovations of the global sushi community.

10. Famous Chefs and Revered Figures

Japan’s Legends

- Jiro Ono – The zen master of sushi

- Takashi Saito – Former 3-star chef, now leading Sushi Saito

- Hideki Ishikawa – Fusion of kaiseki and sushi

Global Stars

- Nobu Matsuhisa – Sushi’s international ambassador

- Masaharu Morimoto – Iron Chef with elegance

- Naomichi Yasuda – Bringing Tokyo-style to New York

11. The Rise of Imposters and Cultural Theft

Chains and the Death of Craft

Sushi chains like Yo! Sushi, Sushi Express, and grocery-store trays sell mass-produced rolls wrapped days in advance. This dilution of the art has led to frustration among Japanese chefs and purists, who see their traditions reduced to fast food.

Untrained Chefs and Dangers

Improperly prepared sushi can be dangerous—parasites, poor hygiene, and unskilled knife work can cause illness. In Japan, licensing and certification are required, but in many countries, anyone can open a sushi bar.

Appropriation vs. Appreciation

There’s a growing debate over who can make sushi, how it’s labeled, and what constitutes disrespect. Cultural appreciation involves learning, honoring, and crediting the source—not just copying for profit.

12. The Philosophy Behind Sushi

Wabi-Sabi and Simplicity

At its core, sushi embodies wabi-sabi: the beauty of imperfection and impermanence. A piece of sushi is fleeting. It cannot be reheated, stored, or duplicated. Each one is a moment—unique, precious, and unrecoverable.

Mindfulness on a Plate

Sushi teaches silence. A great sushi experience involves minimal talking, intense observation, and focused tasting. It is a form of meditation, with the chef as guide and the food as teacher.

The Triangle of Connection

The shokunin (craftsman) prepares the fish, the guest receives it, and the ingredient offers its life. This sacred triangle defines the sushi experience—one of respect, balance, and humility.

Conclusion: Sushi’s Living Legacy

Sushi is not a trend. It is not just food. It is an evolving expression of culture, care, and connection. From the murky rivers of ancient Southeast Asia to the gleaming counters of Tokyo and the neon-lit streets of New York and London, sushi has traveled far—but never forgotten its soul.

Its masters guard ancient truths. Its fans chase new thrills. Its legacy stands balanced between reverence and reinvention.

In sushi, we find something few cuisines offer: the ability to taste time, touch tradition, and experience the world on a single plate.