A Forgotten People on a Stolen Peninsula

In the shadows of global politics, few ethnic groups have endured such profound injustice and persistent marginalization as the Crimean Tatars. Native to the Crimean Peninsula for centuries, they have faced cycles of oppression, forced displacement, and cultural erasure. From the brutal deportation ordered by Joseph Stalin in 1944 to the modern-day crackdown under Vladimir Putin’s regime, the story of the Crimean Tatars is a powerful narrative of survival, identity, and resistance. This article traces their rich history, examines their painful diaspora, and explores their continued fight for justice and homeland recognition in today’s politically volatile Crimea.

Chapter 1: The Historical Roots of the Crimean Tatars

The Crimean Tatars are a Turkic ethnic group indigenous to the Crimean Peninsula. Their identity formed over centuries of settlement, blending the legacies of the Turkic Kipchaks, Mongol Golden Horde, and local Crimean populations. By the 15th century, the Crimean Khanate emerged as a significant power in the region, becoming a vassal of the Ottoman Empire while maintaining relative autonomy.

For centuries, the Crimean Tatars developed a unique culture, language, and political structure. Their cities, especially Bakhchysarai—the capital of the Khanate—flourished with Islamic scholarship, architecture, and trade. But the decline of the Ottoman Empire and the rise of Russian imperialism soon cast a dark shadow over the Tatars’ independence.

Chapter 2: Russian Annexation and Imperial Oppression

In 1783, Empress Catherine the Great annexed Crimea into the Russian Empire. This marked the beginning of a long period of marginalization and persecution for the Tatars. Russian authorities implemented Russification policies, seizing land from the native population, encouraging Russian and Ukrainian settlement, and pushing many Tatars into exile, especially to the Ottoman lands.

Throughout the 19th century, waves of Crimean Tatars emigrated to Turkey and other parts of the Middle East. By the early 20th century, their population had drastically decreased. Despite their loyalty to their homeland, the Tatars remained second-class citizens in their own land, with few rights and little political representation.

Chapter 3: The Soviet Era and Stalin’s Genocidal Deportation

After the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the subsequent formation of the USSR, the Tatars briefly experienced a cultural revival under the Soviet policy of korenizatsiya (indigenization). However, Stalin’s consolidation of power in the 1930s reversed this progress.

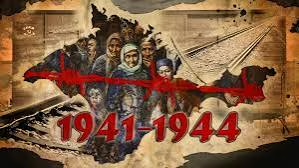

The most traumatic event in Tatar history occurred on May 18, 1944. In a single operation, ordered by Joseph Stalin and executed by the NKVD, nearly 200,000 Crimean Tatars were rounded up and deported from their homeland to Central Asia, primarily Uzbekistan. They were falsely accused of collaborating with Nazi Germany during World War II—a claim never substantiated and broadly condemned by historians today.

The deportation, known among Tatars as Sürgünlik, was carried out with brutal efficiency. Families were forced into cattle trains with little food or water. Thousands perished en route or shortly after arrival due to starvation, disease, and exposure. It is estimated that nearly half of the deported population died within the first few years. Their homes, mosques, cemeteries, and cultural landmarks were destroyed or repurposed by the Soviet authorities. Crimea was ethnically cleansed, and the Tatar name was erased from maps and official documents.

Chapter 4: Life in Exile: Survival, Resistance, and Identity

For the Crimean Tatars, exile was not the end—it was the beginning of a long and painful struggle for justice. In Uzbekistan and other Soviet republics, they lived under surveillance, in poverty, and faced widespread discrimination. They were banned from returning to Crimea, even after Stalin’s death in 1953.

Throughout the 1960s to 1980s, a powerful nonviolent civil rights movement emerged among the Tatars in exile. Activists, writers, and intellectuals petitioned the Soviet government, raised awareness through underground samizdat publications, and organized protests. Despite KGB repression, the movement persisted and gained international attention.

One of the most prominent figures was Mustafa Dzhemilev, a human rights advocate who became a symbol of peaceful resistance. He was imprisoned multiple times but never gave up the fight for his people’s right to return to Crimea.

Chapter 5: The Return Home After the Fall of the USSR

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 opened the doors for a partial return of the Crimean Tatars to their ancestral homeland. Thousands made the difficult journey back to Crimea, only to find their homes occupied and their land redistributed.

Ukraine, which gained independence in 1991 and inherited control over Crimea, provided some legal recognition and limited support. However, the Tatars remained marginalized—without adequate housing, jobs, or political power. Nonetheless, they rebuilt their communities, revived their language and traditions, and began restoring mosques and cemeteries.

The Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People, a representative body formed to advocate for their rights, became an essential political force. Though underfunded and often ignored by Ukrainian authorities, it gave the Tatars a voice and organizational strength.

Chapter 6: Putin’s Annexation of Crimea and Renewed Repression

In 2014, Russia annexed Crimea in a move widely condemned as illegal by the international community. For the Crimean Tatars, it was a nightmare repeating itself. Once again, they were under the control of a regime that sought to suppress their identity and silence dissent.

The Mejlis was banned by Russian authorities and labeled an “extremist organization.” Many Tatar leaders were arrested, exiled, or disappeared. Mosques and Tatar media outlets were raided or shut down. Education in the Tatar language was restricted, and surveillance intensified.

Under Vladimir Putin’s regime, the Crimean Tatars face systemic human rights violations. Organizations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have documented arbitrary arrests, torture, and intimidation against Tatar activists. Russia’s goal is clear: to erase opposition and assimilate the peninsula under Moscow’s iron grip.

Chapter 7: International Response and Ukrainian Solidarity

Ukraine has largely recognized the plight of the Crimean Tatars. In 2021, President Volodymyr Zelensky announced the establishment of the Crimean Platform, a diplomatic initiative to coordinate international efforts for the de-occupation of Crimea and the protection of Tatar rights.

Many Western governments, including the United States and European Union, have imposed sanctions on Russia over the annexation. Yet, enforcement remains inconsistent, and international attention has often shifted to other global crises.

Still, the Tatars continue to raise their voices on international platforms. The diaspora in Turkey, the U.S., and across Europe actively campaigns for awareness and justice. May 18 is now commemorated as a day of remembrance for the victims of the deportation, keeping the memory alive.

Chapter 8: The Struggle Today: Living Under Occupation

As of 2025, the situation for Crimean Tatars remains dire. Estimates suggest that over 100 Tatar activists are imprisoned under fabricated charges. Russian state propaganda portrays them as terrorists, while the real goal is to silence their demands for freedom and self-determination.

Young Tatars face daily challenges. University access is limited. Cultural expression is suppressed. Families live in fear of police raids and political persecution. The rebuilding of their society has been frozen under occupation, and many are once again fleeing into exile.

Despite these hardships, the Crimean Tatars have not lost hope. Online platforms, international NGOs, and underground networks continue to support education, preserve culture, and document abuses. The community’s resilience is stronger than ever.

Chapter 9: Cultural Identity and the Power of Memory

The preservation of culture has been a key strategy in the Crimean Tatars’ survival. Music, language, literature, and oral history remain vital tools in keeping their identity alive. Traditional dishes like chebureki, songs of exile, and the Tatar language are passed down with reverence.

Institutions like the Crimean Tatar Academic Lyceum and media outlets like ATR TV (now broadcasting from Ukraine due to exile) play crucial roles. Online education has helped maintain Tatar identity among youth despite the repression.

Even in exile or under occupation, the Crimean Tatars have shown the world the power of cultural resistance. Their memory is their armor.

Chapter 10: A People’s Unbreakable Will

The story of the Crimean Tatars is far from over. They have been driven from their land, erased from maps, and hunted by powerful regimes. Yet they endure. From the Khanate of Bakhchysarai to the camps of Uzbekistan, from Soviet prisons to Putin’s occupied Crimea, the Tatars have never stopped fighting for justice.

Their struggle is a symbol of human resilience, national dignity, and the right to exist. It is a reminder that even in the darkest chapters of history, the will of a people can outlast tyranny.

Conclusion: Hope for the Future

Though the road ahead remains uncertain, the Crimean Tatars continue to fight—not just for themselves, but for the soul of Crimea. They envision a future where their children can live freely on their ancestral land, speak their language, and practice their faith without fear.

The world must not turn away. The cause of the Crimean Tatars is a call to justice, a demand for historical accountability, and a plea for peace. Their story deserves to be told, remembered, and honored—until the day they are free again.